To illustrate my point, just compare the coverage of the Indian farmer protests to that of the 6 January riots in the US Capitol. Even if you watch the evening news every night, and even if, when you do, one after the other you watch all the bulletins, you’d hardly be aware that, since the northern summer last year, thousands of Punjabi farmers have been taking to the streets to protest new laws introduced by the Modi government. Channel Nine and even the ABC have largely left the story alone and, as a result – outside of the Covid crisis – one of the biggest stories of the past 12 months is being ignored in my country.

Not a bot …

Part of the problem with the Punjabi protests lies in the difficulty of finding out details. This can come down to as small a thing as the lack of language skills, and while many people are illiterate in the Punjab, the culture there is different from the rest of India. People have a firm understanding of who they are, and they are very compassionate and proud.

“Punjabis are very big hearted,” says a friend I spoke with about the crisis. They have a strong ethnic identity, making the famous Bangla music, and have exported the equally famous tandoori food to any number of countries worldwide. This diaspora is also a source of strength because it means that Punjabis are closely involved with the global political order, especially that which obtains in the developed West. Punjabi farmers produce a lot of the grain consumed in India – I have been told 20 percent of the country’s wheat, for example – so farmers there know their own importance. They are physically large and strong – my friend also, casually, told me – and their character is equally generous and expansive. Supporting fellow Punjabis is important to them, and many would be prepared to take extreme action rather than give way.

Even within India there is, apparently, a lack of credible information, and now that the government is working to silence journalists, it is hard even for Indian people to find out the truth of the case on the ground in New Delhi.

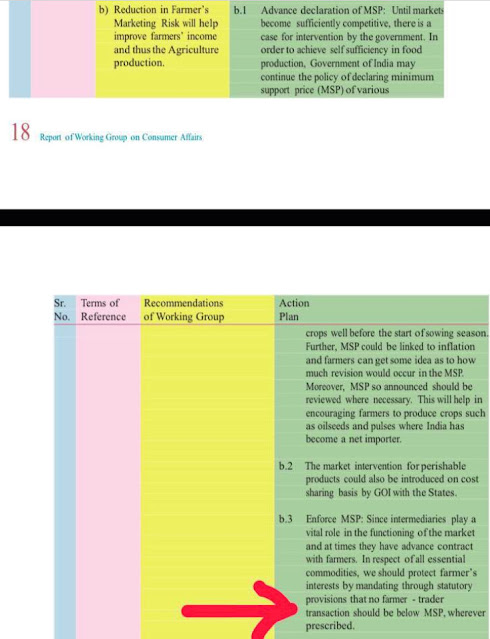

The offensive laws are aimed at making it possible for farmers – many of whom are small operators – to enter into agreements with distributors that set prices according to the action of supply and demand, rather than (as currently happens) based on a government-controlled price. But how this is to exactly function, and even the nitty gritty of the legislation – very little of this has appeared in public and because illiteracy is widespread it is hard for the truth to find the means to be communicated.

The BJP controls much of the media as well as having powerful friends in business, so its position is the dominant one.

The government thinks that, by silencing protest leaders – such as labour activist Nodeep Kaur – they can quell unrest and drag the country back to a state of calm.

Despite ubiquitous connection – “The most remote villages have mobile phones,” says my friend – the Government of India has reportedly had at least one YouTube video pulled down and has reportedly threatened Twitter executives with detention if some tweets are not removed from the site. Many people however flounder in a sea of vagueness. A lack of focus makes it easier for bad actors to sway individuals to behave in a certain way, and makes it almost impossible for the general public – especially in the West – to form a reasoned understanding of the case.

Embarrassment in the face of international criticism is a real threat. Most Indians – even if they are no longer poor – remember what it was like to be poor, so are wary of any trouble or discord, which they identify with a shameful state of vulnerability. And the Indian middle class is growing with, my friend says, most protagonists in Bollywood movies these days being rich. Gone are the days when, on the silver screen, a struggling poor man makes good.

Meanwhile, there are further developments that would hardly even enter into an Australian news story. Some people have been imprisoned by the government for speaking out in support of the protesters. There have been beatings and even torture. The government is attempting to silence its enemies by cutting their access to the internet and to electricity – though friends and family can still bring them food in order for them to survive.

Of course not everyone is singing from the same song sheet.

This individual looks legit (see below Twitter profile screen). Not, at any rate, a bot.

Despite so many Indians being farmers, the government can use nationalism – Punjab has attempted to attain independence before – and religion – Punjabis are largely Sikh, not Hindus – to divide and conquer.

It seems that there is still a way to negotiate.

So whatever happens we can only hope that it takes place in the public sphere. So far, coverage of this critical issue has been abysmal. Such coverage is important not just for Indian farmers – and not just for Indians. It’s important for all of us because the democracy project has to be seen to succeed, and not just succeed. Just as open justice demands the participation of the media in court trials, in the polis itself both sides need to be heard.

We might even get a chance to have a bit of a laugh.

In his book ‘All News Is Local’ Richard Stanton discusses at length a phenomenon where events that might serve to illustrate global standards are usually ignored by the media in favour of the story with a local angle. If we want to find better accommodation of such ideas as international government – we already have many such organisations, such as the UN and the IMF – then we need to improve the level of coverage of issues such as the Indian farmers’ protests.

On 19 October 2007 I attended a talk given by Stanton (see photos below) at the University of Sydney where I was enrolled and where Stanton taught. The talk was on account of the publication of his book.

No comments:

Post a Comment